Yacoub Artin Chrakian: 'England in the Sudan'

In 2015, when I was still a BA History student, a movement which began at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, spread to the University of Oxford in the UK. That movement was the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign demanding that the statue of Cecil Rhodes, a 19th century imperialist and mining magnate deeply associated with a history of colonial expansion, exploitation and white supremacy in South Africa, should be taken down. This movement sparked a debate about decolonising university campuses and the roles statues have as symbols of oppression. Historians, regardless of the objectivity we may claim to espouse, are also products of our times and I remember as a student in the UK being in these debates about statues and the memory of figures who held views normal for their time but now considered racist which justified an imperial ‘civilising mission’.

In this series ‘Yacoub Artin Pasha’ we explore a figure who was arguably one of the Armenians most adjacent to European colonial power in history, with views which reflected that. The other articles in this series will explore the line of Armenian bureaucrats in Egypt that Yacoub Artin Pasha hailed from and what the letters related to Yacoub Artin Pasha in the AGBU Archive in Cairo tell us about the Sudanese-Armenian community.

This article contains historical quotes and references that exhibit racist views. They are presented for historical study only. We believe it is important to acknowledge them rather than erasing or altering them, as a reminder of the ideas that existed and still continue to shape our world today. We include this material to preserve the historical record and to better understand the context in which Sudanese-Armenian life unfolded.

‘An enlightened Egyptian’

Yacoub Artin Chrakanian, better known as Yacoub Artin Pasha, was born on April 15 1842 to Artin Bey, an Armenian originally from Constantinople who had settled in Egypt and risen up the ranks in the Egyptian bureaucracy of Muhammed Ali. In a previous article we spoke about this small group of Armenians who thrived due to their language skills as bureaucrats for Muhammed Ali and his successors.

Yacoub Artin Pasha followed in the footsteps of his father who worked in the Egyptian government, and became famous for reforms in education earning him the title ‘Al Ustaz Al Kabir’ or the ‘Great Teacher’. He was fluent in Armenian, Turkish, Arabic, Persian, Greek, Latin, Italian, English, and French. As an education minister, Yacoub Artin Pasha championed progressive ideas aiming to increase public accessibility to education. He also founded Cairo Teachers Training Institute, the Siyufiyyah School for Girls, the Immaculate Conception School for orphan girls and the Yeghiayan Educational Fund for the needs of orphans.

He was a polyglot, an accomplished man, writing numerous books in French about Egyptian education, society, geography and even one about the ‘Coat of Arms of the Orient’. But what of his character? Muhammed Rifat Al-Imam, a prominent historian of Armenians in Egypt, points out his gentle and neutral manner, avoiding controversial or provocative statements. In this way he obscured his political leanings, maintaining friendly relations with Khedival Egypt, the British, the French and the Ottomans.

The British press commented on his character, with the Spectator stating ‘he knows Egypt well, he knows Englishmen well; he knows Europe well’. The Atheneum continues: ‘As a Minister of Education in Egypt for a quarter of a century he has been in close touch with native thought and opinion’. They also described him as ‘one of the most popular figures in the European society of [Cairo]’ who was ‘too honest and too frank to play the sycophant. He is also too clear sighted to be imposed upon’. The Times literary supplement summed up the reputation he had with: ‘no Egyptian official has stood in higher esteem’.

Through his achievements, writings and reputation it's clear he was a respected politician with European ideals in Khedival Egypt. He also never lost touch of his Armenian roots and after the establishment of Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) in Cairo in 1906 he would have a prominent role there too. Yacoub Artin Pasha was a quintessential figure from the tradition of Armenian bureaucrats in high positions in Egypt during the 19th century, a tradition starting with Boghos Bey Yousefian and which included Boghos Nubar. While being Egyptian-Armenian, these bureaucrats were a strata above the rest of the Egyptian-Armenian community who Lord Cromer, the governor general of Egypt, had described as ‘shopkeepers’.

In 1908 Yacoub Artin travelled to Sudan and detailed his journey in his book originally in French called ‘England in the Sudan’. The book was published in 1911 by Macmillan and Co in English and translated by George Robb. During his travels he documents his interaction with Sudan’s early Armenian community who had become established there in the nine years between his journey and the British conquest of Sudan.

Yacoub Artin Pasha’s journey to Sudan

When the British first started sailing in search of fame and fortune, they would not have predicted that one of the consequences of their empire a few centuries later would be a winter sun destination for wealthy Brits. Not unsimilar to today, well off Brits loved escaping the winters of the British Isles for a safe sunny destination where Britain had a presence. Egypt was at one point that ‘winter playground’, but with the British conquest of Sudan, that also opened up as a destination for the more adventurous.

In September 1907 a recently retired Yacoub Artin was in Edinburgh as a guest of Archibald Sayce, a professor of ancient history at Oxford University. Sudan came up in conversation, and they conceived the idea to journey there together. Yacoub Artin Pasha had been before in 1902 but only going as far as Khartoum. So on 9th November 1908 with the blessings and invitations of Sir Reginald Wingate, the Governor General of Sudan at that time, they set out from Aswan to Wadi Halfa. The journey took them to Khartoum, where they were guests of Sir Reginal Wingate, before continuing down the White Nile to what is now South Sudan. On the way he detailed his audience with the British administrators, the local geography and the various tribes and ethnicities of Sudan.

No ordinary tourist

What made the book special compared to the many accounts from Brits in Sudan was the Pasha’s unique capacity to be understood by both Europeans and ‘natives’. The Manchester Guardian described him as a man of ‘broad’ sympathies who ‘knows what he is talking about’. He displays this in the book, in some cases acting as a translator, elsewhere he comes across Egyptian bureaucrats in Sudan who he has a pre-existing relationship from their time working together in the Egyptian government. The British press also recognises that his language skills, his reputation with Egyptians and Europeans, and his understanding of the ‘east’ makes him able to discern more information and realities than the standard observer. The Journal of Royal African Society has even gone as far as to suggest that in ‘all probability’ he was ‘welcomed as a co-religionist’ which meant he could find out the ‘true feelings and views’ of people in Sudan.

He suggests this in his own words as well. For example, he mentions the British and their prejudice against Islam and lack of understanding of the religion when discussing slavery in Sudan. When discussing Sudanese in the British army and the need for officers to belong to ‘powerful and respected tribes’ he mentions the ‘democratising influence of Islam’, which again alludes to his deeper understanding of the local cultures and faiths compared to the British.

Armenians in ‘England in the Sudan’

Like Yacoub Artin Pasha, the Armenians in Sudan also held a position somewhat between the ‘natives’ and the British. Unlike Yacoub Artin Pasha, the early Armenians in Sudan were not high level bureaucrats, or people known in European high society. They were, more often than not, Armenians seeking opportunities away from what was becoming a ravaged homeland. Yacoub Artin Pasha’s account of his interactions with Armenians in Sudan is a valuable source or understanding the early Armenians who migrated to Sudan in the decade before his travels. In the decade after his travels they would begin to take shape as a community before seeing their numbers swell with Genocide survivors arriving.

The Pasha interacts with three Armenians in Kamlin, the first he describes is Krikor Bozadjian, who perhaps via mistranslation is named ‘Kirtar Bazadjian’ in the book. The description of him is as follows: ‘Kirtar Bazadjian, is director of the Government farm. I have paid a visit to the farm, the area of which is about 150 feddans. It is exceedingly well kept, and experiments are carried on with different kinds of cotton, wheat, maize, and Sudanese beans. The farmer, a good type of Armenian, a well-set-up man and a hard worker, is from Tokat. He has a wife and two children, and seems quite contented with his lot ; in his own country he used to be a tobacco-planter’.

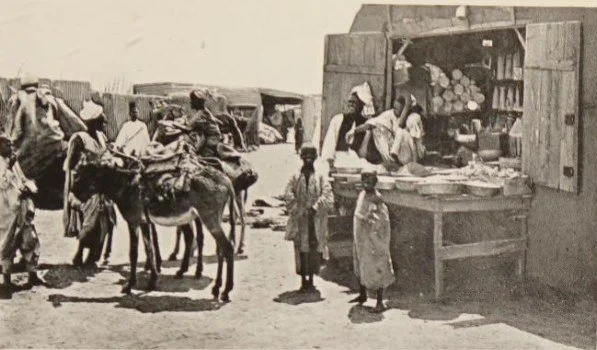

The second is Dihran Kasbarian, a ‘bakkal’ or merchant operating a ‘baqala’ (shop): ‘A merchant from Constantinople; he married a young Armenian girl at Khartum last August, and is quite happy to be settled here, where he is the only bakkal’. And the final in Kamlin is Leon Limondjian, a mechanic in Government employment ‘who lives here with his mother, and both of them seem perfectly happy’.

In Rufaa the Pasha describes how: ‘On our way back to the steamboat we passed through the market-place, where I saw the shop of two Armenians who are partners in a ‘general stores’. They informed me that they have been established at Rufa’a for two years, and that their business is a prosperous one. They are the only two foreigners in the town’. In Omdurman the Pasha says he found ‘merchants and workpeople’ in the shops and market including ‘Turks, Persians, Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Austrians, Italians, etc’.

At Mashra’a el Ziraf, at an india-rubber plantation: ‘the head of the plantation is an Armenian, Monsieur Nourian, son of Nourian Effendi, a Councillor of State at Constantinople, whom I used to know’. ‘Monsieur Nourian lives quite alone here with about forty Arabised and Islamised negroes that come from Wad Medani on the Blue Nile’. He interacted again with Nourian on his return journey: ‘When we were taking in firewood at Mashra’a el Ziraf we once more saw M. Nourian, but he was unable to come aboard owing to the high wind and the agitated state of the water.’ On one of his days in Khartoum: ‘at four o’clock I had tea with Madame Abcarius, nee Singer. Monsieur Abcarius had, in honour of our visit, invited a number of Sudanese Arabs to recount to me some of the kadduta or folk-lore of the country’.

What do these accounts of the Armenians in Sudan in 1908 tell us? It suggests the Armenians like the other Christian communities were economic intermediaries rather than political or administrative actors (with the exception of Abcarios who we will explore more in a future article). A dialogue between the Pasha and a banker in Khartoum, Mr Singer, gives us a clue as to why this is the case. The banker states that private enterprises will struggle in Sudan because of the ‘tendency of the Anglo-Egyptian Government to monopolise everything’. He describes the British Government as the ‘head of a vast monopoly, and which crushes all individual enterprise’. Moving on from the economy to his personal business methods, Mr Singer states: “I do not count upon the natives: that would be too risky a business, for they lack good faith and are devilishly litigious".

Mr Singer’s comments provide us a clue as to how these Armenians established themselves in Sudan. Similar to our findings from our research on the early Armenian journeys to Sudan, it suggests that there was a gap in the colonial enterprise because of the British social and economic distance from the ‘natives’ in addition to a lack of white settlers from Britain such as those in other colonies. Equipped with language skills, a history of co-existence with different cultures and in search of economic opportunity, the Armenians, like the Greeks and others had a mostly commercial role in this gap.

Though this gap had an economic element and allowed Armenians to succeed in commerce, it existed due to the racist attitudes of the British. Heather Sharkey in her book, Living with Colonialism: Nationalist and Culture in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan explores the British racial hierarchies and how ‘natives’ were divided into four groups (‘Arabs’, ‘Blacks’, ‘Berberines’ and ‘Muwallads’) at an institution like Gordon College and how these were continuations of the racial hierarchy employed during Turco-Egyptian rule.

A quote from Yacoub Artin Pasha’s book also adds to our contextual knowledge here: ‘One curious feet I have observed is that, whilst the School is attended by Arab and Negro Sudanese, Egyptians, Copts, Abyssinians, and even one Persian, there is not a single Turk.. Prof. Sayce is right in defining the Sudan south of the 25th degree of latitude as “No white man’s country”’. This quote suggests that Yacoub Artin Pasha and Sayce did not consider the other communities as ‘white’, a designation reserved only for British and Europeans.

Nonetheless within the categorisation of peoples in Sudan in this era there does not seem to be any official or legal category for non-British, non-native communities such as Armenians, Greeks, Italians or Jews. While Armenians were respected over the ‘natives’ by the British, they were also not considered British or provided British citizenship. Future articles will explore this further using other sources such as personal accounts and photographs to demonstrate that the economic gap was also a racial gap between ‘natives’ and the British - the Armenians, being respected by both and able to communicate with both, were able to succeed in commerce in this gap.

The account of Monseiur Nourian also speaks to this. He lived geographically isolated in a rural environment alongside Sudanese and yet was comfortable with this circumstance. As the community becomes established and grows we will see Armenians using their languages and cross-cultural knowledge to be comfortable filling the economic gap that existed in Sudan’s rural and urban environments. Mr Bozadjian’s innovative farm was also a sign of things to come, with Armenians being pioneering in Sudanese industry over the next half a century, establishing many first in kind factories and businesses.

Ultimately, the Pasha’s description is not of a community but individuals. Some are employees of the government, some are traders and some are operating private enterprises. They are spread geographically across Sudan’s difficult climates, mostly isolated and engaging in various economic activities across Sudan. He doesn’t describe any community structures or community life which we know emerged over the coming decade.

Imperial stalwart or man of his time?

Yacoub Artin Pasha’s account reflects the prevailing imperial, colonial and European views of his time. Even for a historian who reads about the British Empire and its subjugating policies in Sudan, it was a difficult read because it is a reminder that it was only approximately three generations ago that the prevailing western view was deeply racist, the remnants of which remain and continue to impact our world today.

Throughout his letters he provides many reflections on ‘civilisation’ including annexes at the end. This subject is unusual today, but at the time there were many debates regarding the nature of civilisation to seek to justify colonialism via a ‘civilising mission’ - a justification for empire and the conquest to ‘civilise backwards peoples’. Yacoub Artin uses his travel in Sudan to provide his own reflections on the debate. He primarily ascribes to the baseline colonial view of the time, that Europe is enlightened and can spread civilisation to the rest of the world: ‘Here in the Sudan is one of these actions, in the execution of which patience is perhaps more necessary than anywhere else to lead the peoples who inhabit the country to the enjoyment of the benefits of the civilisation we offer them’. And he pushes this concept of a ‘civilising mission’ as the reason for Britain being in Sudan: ‘All the men we met have given up their lives to the work of conquering the Sudan and converting the Sudanese to civilisation, with the object of securing the general welfare of the people and their physical and moral progress’. His writings here are for the public, being an astute politician he knew full well the reality of empire and that Sudan’s importance for the British was to secure the source of the Nile and therefore Egypt and the Suez, rather than any grand moral mission.

Another element of the British colonial philosophy he ascribes to is the racial hierarchy which was employed by the British in Sudan. Britain viewed the Arab tribes as more civilised than the ‘blacks’ and this shaped their colonial policy and the Pasha agrees with this and points out explicitly that this is the British policy at that moment and that he thinks it will work as intended: ‘Happily for the Sudanese, the present Government is imbued with these principles, and, therefore, I have not the slightest doubt that the establishment of order and peace in the Sudan, and the material and moral progress of the people, are matters of the near future.’

He also romanticises the tribes of southern Sudan. The common perception of the time was that such tribes were uncivilised and primitive, though there were narratives in European writing that glorified what can be termed these tribes as ‘simple’ and living a life more attuned with nature. For example, on the Shilluk tribe he said: ‘I would willingly pass several months in the midst of these good folk in order to learn the meaning of virtue in both the ancient and the modern sense of the word.’ He uses the tribe as a mirror to comment on the moral degeneracy of European society: ‘Are honesty and fidelity virtues natural to that society which we stigmatise as savage, and yet so unnatural in our civilised society as to need to be inculcated’.

These types of comments lend itself to him arguing for a theory of ‘civilisation’ which varies from the mainstream of the time suggesting that the peoples of Sudan aren’t inherently ‘uncivilised’, but that the circumstances in Sudan are the fault of their previous rulers, the Turco-Egyptians and the Mahdi: ‘The unfortunate people have, after ten years’ experience, just begun to show confidence in the beneficent and reparative efforts of the Government’.

In commentary at the end of the book he refers directly to the debate taking place in his day on this subject. He introduces the theory advocated by the British scientist John Hunter that ‘civilisation’ is connected to ‘whiteness’. The work of Thomas Henry Huxley is then quoted to counter that and argue that civilisation is not inherent to a certain race, and there is no ‘biological superiority’ based on whiteness. He agrees with this theory arguing that the Europeans could regress into ‘barbarism’: ‘When these people reach a period of civilisation, may not other peoples, who at present call them barbarians, themselves fall back into barbarism and savagery in their turn?’. By suggesting that civilisation is not something genetic or inherent to a certain skin colour, he is proposing that societies can achieve civilisation or more to his point, a thing the British can help the Sudanese achieve. And he confirms this when stating that Egyptians were also at one point ‘ignorant superstitious people’ and that through enlightenment and progress the Sudanese, will ‘give place to an educated, active, and civilised people’.

Reception to ‘England in the Sudan’

Description: The Atheneum’s review of ‘England in the Sudan’

Location: NA

Source: Sudan Archive at Durham University

Following translation and release, the reviews of the book from the British press give us an indication of how it was received. But before diving into that, in the Durham Archives and specifically the document collection of Reginald Wingate, the Governor General of Sudan, we discovered a letter from Wingate to the Pasha about the book. In the letter he focuses on its commentary regarding the ‘black races’, agreeing with most of his assertions: ‘Anyone who has had prolonged experience in black countries will agree that under proper sympathetic treatment there is a great future for the black races’. Wingate refers to the debate of the day on the subject of ‘civilisation’ even placing the Americans and their views on race on the other side of the debate criticising their attitudes: ‘this wholesale lynching [in America]… is to be most strongly depracted’.

This letter from Wingate suggests that the Pasha’s commentary on civilisation and race was not just something he mentioned in passing that fell on deaf ears - he was actively weighing in on a theoretical debate taking place at the time, a debate which was prominent of the minds of policymakers and colonists like Wingate.

The British press contains both positive and negative reviews of the book. The Times Literary Supplement draws attention to him being a well placed observer on account of his language skills, his personal connections with those from Egyptian Government Schools and his experience with ‘natives’: ‘Wherever he went in the Sudan he found old pupils from the Egyptian Government schools who gratefully remembered him and were ready to talk to him perhaps more freely than they would have talked to an English official’. The Daily Chronicle talks about the format of his book as a collection of letters claiming it introduces: ‘familiar touches of human - or I should say, womanly interest’.

The Spectator was critical of his impartiality stating that he has an ‘unwillingless… to declare his opinions’. They go further stating that the Pasha is ‘content’ to provide opinions of those he met but because he refuses to give his own views the book has ‘no independent critical value’ and thus being only beneficial for describing geographies and locations. The Yorkshire Daily was critical of the letter format arguing it is a lazy approach: ‘The Pasha has merely reprinted his letters home! … We really expected something different from his Excellency’. They were also critical of his view on race: ‘One cannot come to profitably close quarters with the problem of Europe in Africa when the last thirty years are not distinguished from the “thousands of years” which went before for the purpose of theorising on the destiny of the subject races’.

The broad newspaper reception suggests the book was popular upon release with more positive than negative reviews which generally point towards the Pasha using his connections, languages and intercultural knowledge to provide unique observations on Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The press reactions also tell us that the British public miles away from Sudan understood the context of their Empire and the contradiction of what they perceived as their ‘civilising mission’ with the realities of a brutal empire: ‘Our rule is purely military; the Government is a huge monopoly or trust controlling and owning practically everything in the state’. This understanding is summed up best by this line from the Daily Chronicle: ‘We have only been able to do so by means of a despotic sort of benevolence, in which the iron hand has always been more than visible beneath the velvet glove’.

The Pasha from the past

Unlike Rhodes mentioned at the beginning of the article, the memory of Yacoub Artin Pasha, his theories and actions, have not echoed in our society today - he is a forgotten figure, and his ‘England in Sudan’ has seldom been studied or read in the more than a century since its release. It is for us, first and foremost, a unique early source describing early Armenian life in Sudan. The picture he presents is of individual Armenians, geographically spread, engaging in various economic activities. The account alludes to the commercial gap created by the British Empire that the Armenians operated in and we will explore this gap in future articles via different sources.

Beyond that, the whole book highlights the Pasha’s unique stance as a cross-cultural intermediary - someone of the eastern world who understands the western world. The British press emphasised a point which is clear in the text that the Pasha is not British but also not a ‘native’ and it is this that makes the book better than the standard British travel account through Sudan. This same positionality but within a different historic and socio-economic context is also what made the Sudanese-Armenians a unique community that could thrive in the commercial gaps created by British colonialism in Sudan.

Finally, the article has not ignored the reality that Yacoub Artin Pasha was a man who held the prevailing European views of the time. The analysis has engaged with those difficult-to-read themes as a necessary context to understanding the author, but also as a context of British colonialism which is the socio-political setting in which the Sudanese-Armenian community existed. It is those views which underpinned the colonial ‘civilising mission’ and those views which continue to impact our world today.

Notes:

You can read more about Yacoub Artin Pasha in Arabic here by Dr. Mohamed Refaat Al-Imam, the expert in Egyptian-Armenian history: “Artin Pasha and Egyptian Culture,” Aztag Arabic Supplement for Armenian Affairs, 13 August 2018, archived on the Wayback Machine on 31 July 2024

For Arabic-language sources on the Egyptian-Armenian community, including archival research, see the works of Muhammad Refaat al-Imam. For more information, the Armenian Embassy’s website has a summary on the history of Armenians in Egypt. There are also references and sources in our article about Egypt’s Armenian community.

All the newspaper reviews in this article were from 1911 and accessed via the Sudan Archive at Durham University in August 2025 in the files of ‘General Sir (Francis) Reginald Wingate’ (reference code GB-003-SAD) and the newspaper cuttings with reviews of the book specifically can be found under the following code: SAD.299/1/237,243-2444,251,253,255,260,283

The quote from Lord Cromer regarding Armenians being ‘at most neighborhood shopkeepers’ is from Bedros Puzant Torosian, In Search of Haven and Seeking Fortune: The Economic Role of Ottoman Armenian Migrants in British-Occupied Egypt (1882–1914) (M.A. thesis, American University of Beirut, Department of History and Archaeology, 2019) which can be accessed here.

Yacoub Pasha Artin, England in the Sudan, trans. George Robb (London: Macmillan and Co., 1911) can be accessed here. This article will not give specific page number references for each quote from the book, but the link has a search function which can be used to look up any quote found in this article.

‘Winter playground’ to describe Egypt was a term used by the Times Literary Supplement to describe Egypt (Durham Archives SAD.299/1/237)

The EA Stanton review is featured in is from E. A. Stanton, “England in the Sudan,” Journal of the Royal African Society 10, no. 39 (April 1911): 274–284, published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society

Yacoub Artin Pasha does not state that Abcarius as an Armenian, but we know via the AGBU archives and other sources that there was a N.Abkarian who was a judge in Khartoum, and we suspect this Abcarius is the same as mentioned in Yacoub Artin Pasha’s book who he said had married an Englishwoman ‘Singer’. Abcarius is a common Anglicisation of the Armenian name Abkar or Abkarian in English.

An interesting observation is that he calls both Abcarius and Nourian ‘Monseiur’ which he does not use to refer to the other Armenians. This could be irrelevant or a title he used in that given letter or a translation inconsistency by Robb. But considering both Nourian and Abcarius seem to have upper class backgrounds with Abcarius being a judge and Nourian’s Father previously having been a councillor in Constantinople, we can infer these Armenians were held in higher regard by him. This is particularly the case for Nourian who is mentioned as the son of an ‘effendi’ and he even knew Yacoub Artin Pasha before, suggesting he interacted in the circles of upper class or elite Armenians in Cairo or Constantinople.

The Egyptian Copts in Sudan also held prominent commercial roles but as the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was formally a joint imperial venture many Egyptians also staffed the colonial administration and military until the 1924 revolution and mutiny following which the Egyptians were gradually removed from Sudan’s government.

Interestingly Stanton in his review of the book in the Journal of the Royal African Society specifically mentions this dialogue with Mr Singer criticising the validity of his assertions regarding governmental monopoly. Stanton continues calling out Mr Singer for not giving enough credit to the colonial government who gave a favour in his case over land near Khartoum which he claims ‘that under no other flag would he have won his case’ in E. A. Stanton, “England in the Sudan,” Journal of the Royal African Society 10, no. 39 (April 1911): 274–84, published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal African Society.

On nineteenth and early twentieth century debates about civilisation and the so-called civilising mission, see for example John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (London, 1859), where he defends ‘despotism’ over ‘barbarians’ as legitimate if aimed at their improvement; E. B. Tylor, Primitive Culture (London, 1871), framed human societies in stages from ‘savagery’ to ‘civilisation’. For contextual analysis, see Uday Singh Mehta, Liberalism and Empire (Chicago, 1999) and Alice Conklin, A Mission to Civilize (Stanford, 1997).

For more on the racial hierarchy in Sudan see Heather Sharkey, Living with Colonialism: Nationalism and Culture in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (2003).

Another example of the Pasha deviating from standard colonial views is when the Pasha makes an interesting commnet almost mocking the British: ‘During the progress of the dinner I felt as though I were in the midst of a band of lay missionaries whose object was to secure the peace and happiness of the world.’

Glorifying ‘primitive’ tribes has its roots in antiquity with Tacticus, a Roman historian who praised the Germanic tribes seen as barbarians by the Romans for their bravery, simplicity and honor - virtues he claims the Romans had lost. The Pasha refers to Tacitus’ on the Germans in the commentary after the book comparing tribes of Sudan to the Germans in their morality and their propensity to be ‘civilised’. The enlightenment philosopher Jean Jacque Rosseau formalised this concept in his Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men speaking about how civilisation corrupts human beings, and that having a life in a state of nature makes them virtuous. European colonial discourses often adopted this concept to romanticise colonised people as pure, simple and virtuous. Stanton’s review of Yacoub Artin Pasha’s book also points out that the Shilluks and the Dinkas have some of the ‘finest soldiers in the famous Black Regiments of the Egyptian Army, which distinguished themselves in every one of the battles and actions under Lord Kitchener’.

Stay updated:

Stay updated on our latest releases - give our social media pages a follow.

We would love to hear from you, whether it be a reflection on this post, a correction or a suggestion, send us an email at info@sudanahye.com.