Egypt: Discovering Cairo’s Armenian Heritage

‘Um al-Dunya’ (أم الدنيا) is an Arabic expression meaning ‘Mother of the World’ and is used across the Arab world to refer to Egypt. Whether due to its rich soils, its strategic position with access to Europe, Africa and Asia, or the leaders who have ruled it, Egypt has held a position of significance for most of history. Stemming from this, it is home to diverse peoples across religions, cultures and ethnicities. Armenians are also one of these peoples that have come to call Egypt home and have developed a rich history which is part of both Egyptian and Armenian heritage.

Both Turco-Egyptian Sudan (1820-1885) and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899-1956) tied Sudan to Egypt via an imperialist structure. In particular the Anglo-Egyptian era saw the Armenian community in Sudan grow from a few isolated Armenians to a community as an extension of the Armenian Community of Egypt with commercial, institutional and familial links between the two. Throughout the course of this project it has become clear that researching the Sudanese-Armenian community requires some understanding of Egypt’s Armenian history. Egypt’s Armenian community arguably has had the largest cultural, economic or political footprint of an Armenian community in any Middle Eastern country. Due to this, Egypt’s Armenian history has been heavily studied and it continues to make new history today albeit with a smaller community and with its creative legacy continued by the new generations.

Rather than attempting to navigate the dense research on this community which would be many projects and books itself, to get acquainted with this history the project will present a geographic journey. While Egypt and its Armenian heritage has seen many changes through the passing decades, for those willing to look, both Cairo and Alexandria can be ‘open museums’ to Egypt’s Armenian history and this article will follow a journey through Cairo’s Armenian heritage.

‘The Armenian Period’ of Egyptian medieval history: Old Cairo

In a previous article about Armenians in the Mahdiyya and Turkiyya periods of Sudanese history we touched upon Badr Al-Jamali as a Muslim-Armenian vizier of Fatimid Egypt who led an army consisting of Sudanese and Armenian troops to save Fatimid Egypt from crumbling. He also facilitated migration of Armenians to Egypt from their indigenous homelands following the fall of the medieval Armenian capital of Ani. It is due to him and his peers that Gaston Wiet, a specialist in Egyptian history, labeled the Fatimid period between 969-1170 as the ‘Armenian Period’. Badr’s legacy means our journey to discover Armenian Cairo starts in an unlikely place - at an inaccessible mosque on a hill overlooking old Cairo and opposite Saladin’s famous citadel of Cairo - the Juyushi mosque. Christianity is a key element of Armenian identity, and Armenian presence in and outside indigenous Armenian lands have become defined by Armenian churches as a focal point of community. But the thorough research of Seta Dadoyan suggests that in medieval times, there were cross cultural influences between fringe sects and understandings of Christian and Muslim theology that enabled people like Badr Al-Jamali to identify as Muslim Armenian.

Our journey continues toward Old Cairo where other monuments that are part of Badr Al-Jamali’s legacy can be seen including the gates of Old Cairo’s fortifications; Bab al-Nasr, Bab al-Futuh and Bab Zuwayla. The last of which reportedly had many Armenians settled in its proximity. These Armenians brought their crafts and knowledge including the introduction of architectural elements such as rounded flanking towers or ashlar masonry which can be seen on these gates with their resemblance to the fortifications of Ani.

The early community: Fustat

Skipping ahead centuries, Khan al Khalili is a popular market in the heart of old Cairo. In the Ottoman period it was home to many Armenian merchants and in particular, gold and silversmiths. This Armenian community in the 1800s was the smallest of the foreign communities such as the Greek, Italian, French or Jewish and financially was less prominent than these communities with British Consul General in Egypt Lord Cronmer describing the Armenians around the turn of century as ‘neighborhood shopkeepers’.

With a significant number of Armenians, churches were constructed to serve the community. The oldest Armenian church in Cairo can be found near the Fustat area now inside the Armenian Orthodox cemetery. The Saint Minas chapel was originally built in 1843 to replace an older church and thus is among the oldest remaining Armenian structure in Egypt. The graves in this cemetery include famous Armenian figures such as Hamo Ohanjanyan, a Prime Minister of the first Armenian Republic. The cemetery varies greatly in style representing the diversity within the Armenian community in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some are simple wooden graves, others represent great wealth, some have Armenian designs, others Egyptian art deco or gothic. This area also houses the Armenian Catholic cemetery which is built around a chapel which originally functioned as a church. Continuing north from here eventually leads to a road called ‘Nubar Street’ named after Nubar Pasha.

Nubar Pasha has come up time and time again in this project - he was Egypt’s first Prime Minister and held the role multiple times advising the viceroys who descended from Muhammed Ali, an ethnic Albanian who seized power to lead Egypt in the early 19th century. Nubar’s story was the pinnacle in the achievement of the few families of Armenian bureaucratic elite from Ottoman coastal cities such as Smyrna (today Izmir) or Constantinople (today Istanbul) who were favoured by Muhammed Ali and his descendents. The reason for this preference is multifactorial; Muhammed Ali himself is said to have had positive interactions with Armenians in Constantinople when he was a tobacco merchant and viewed Armenians as honest and good workers. Furthermore, Armenians such as Nubar or other figures such as his nephew Arakel Bey Nubarian who governed Sudan or Ohan Dermirjian who became ambassador to Sweden, were of civilian background, representing no military threat while also being skilled bureaucratic operators with familiarity of regional customs and languages. With such significant representation in government, naturally Armenians were encouraged to migrate to Egypt and the Armenian population grew to 10,000 people by 1895. This exclusion of Egyptians from the governing of their own country led to events such as Colonel Urabi’s revolt in the late 19th century. Eventually this bureaucratic elite was replaced by an administration that reflected the growing British influence in Egypt. Nonetheless, Nubar Pasha is still remembered as a significant figure in the shaping of modern Egypt symbolised by an event held at Giza Library on February 16 2025 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his birth featuring contemporary artwork and books as a tribute to his legacy.

Egyptian-Armenians in cosmopolitan Cairo: Downtown

Walking up Nubar Street leads to the area known as Downtown. Nubar Pasha served as Prime Minister for Khedive Ismail, a leader of Egypt who wanted to modernize Cairo to be a ‘Paris on the Nile’. Nubar Pasha was an advocate of modernising, but warned such grand projects were extremely expensive, and would require foreign debt which would facilitate foreign influence. Nubar’s warning eventually became reality, nonetheless Ismail’s vision provides us with downtown Cairo, an area defined architecturally by wide boulevards and grand European style architecture. The importance of this area to Cairo’s social and cultural identity is symbolised by the popular novel ‘The Yacoubian Building’ by Alaa al-Sawany which follows a number of characters from across Egypt’s broad social strata who live in a single building in downtown. The story itself is fictional, but the arto-deco building is real and was designed by Garo Balian (who was from the famous Balian family of architects in the Ottoman Empire) and is named after the Armenian owner Hagop Yaacoubian.

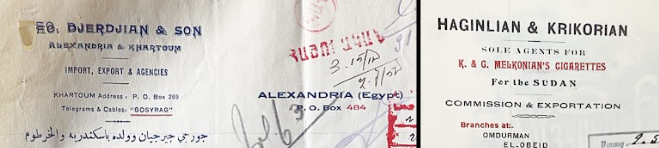

An example of the Armenian presence in this area that is hard to miss is the Armenian Catholic Cathedral near Tahrir Square. Designed in Armenian architectural style, this building stands out as a reminder of the wealth of the Armenian community - that is to have a Church which has stood since 1926 in the heart of Cairo despite all the shifts in society. While the Church is well maintained, most of the Armenians who worshipped there have since left the area. At its peak in the 1940s, Armenians numbered approximately 50,000 people in Egypt and their presence in the downtown area alongside the other foreign communities was impossible to miss. One such famous business that remains Armenian owned to this day is ‘Readers Corner’, a shop that originally sold books but now specialises on artwork and frames. This is a family business and speaking with Hratch who is a member of that family, is a history journey itself. He traces the history of the Armenians who arrived after the Armenian Genocide, with many living in camps in other parts of Egypt or Cairo before setting up shop and creating successful businesses in Downtown. These businesses became some of the most prominent names in their industries such as Vart Studio for photography, or the Matossian Tobacco Company among many, many more.

The nearby area of Boulaq was home to the Kalousdian Armenian School which provided a high quality education to Armenians in Cairo. This school was founded in 1854 as the Khorenian school before being renamed the Kalousdian school after its founder Garabed Agha Kalousd. Continuing through Downtown towards the commercial centre of Attaba, another famous Armenian establishment is the Francis Papazian store which is known for watches, clocks and repairs. The Francis Papazian shop is just off Attaba square where the Casino Opera club once stood before it was burnt down in 1952 as part of the riots against the British and anything that was associated with British or western influence. These riots were part of a series of events that contributed to the downfall of the Egyptian monarchy of Muhammed Ali’s line and the rise of Gamel Abdel Nasser and his brand of pan-Arab nationalist politics. Nationalisation of businesses followed soon after and brought an end to what Hratch described to me as the ‘Ladies and Gentlemen Era’. This era in downtown was defined by cosmopolitanism with adjacency to Europe being the measure of advancement, and foreign communities dominating the business landscape of downtown. The nationalisations led to many of these communities in downtown including the Armenians, emigrating abroad. A famous example of a nationalised business is the Matossian Tobacco Company which was nationalised into the Eastern Tobacco Company, that still continues to be Egypt’s leading manufacturer of cigarettes via the Cleopatra brand. Despite the end of this era, Armenian names continue to be associated with quality in business, so much so that Hratch tells me that some businesses kept Armenian names despite no longer being Armenian owned, because the Armenian name has a reputation for quality.

Moving north from Downtown opposite the Orabi metro station is the Housaper building now known as Alhosabir Theatre. This building was the home of the Housaper cultural association and newspaper, one of many Armenian newspapers published in Egypt. The history of the Armenian press in Egypt goes back to 1865 when Abraham Mouradian established ‘Armaveni’. Since then a number of Armenian newspapers and magazines in different languages have come and gone including ‘Artemis’, one of the first Armenian women’s magazines established by Mari Beyerian in Alexandria, as a platform to explore women’s rights themes and the role of women in the development of Armenian national consciousness. The magazine published for a year with Mari eventually returning to Constantinople where she died during the Genocide. Housaper (from 1913), Arev (from 1915) and Tchahagir (from 1948) are three Armenian newspapers that remain in operation until today and also represent the three traditional Armenian political parties, the ARF, ADL and SDHP, all three of whom were prominent in the organising of the Egyptian-Armenian community.

The community continues: Heliopolis

Walking east on Ramses Street in the backstreets of the Azbakeya neighbourhood is Studio Nassibian. Now a theatre, Studio Nassibian is a reminder of the role Armenians held in the film and TV industry for which Egypt became famous in the Arab world during the 1940 and 50s. Armenians worked backstage to produce the entertainment, but also in front of the camera via stars such as Nelly or Lebleba. The Armenian contribution to Egypt’s entertainment industry is part of a wider active Armenian participation in the Egyptian creative scene ranging from painting to music to sculpting and more. This area also houses the St Gregory the Illuminator Church, a building that has remained majestic since its construction in 1928, and opposite it the Patriarchate from where the Patriarch leads the Armenian church of Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and South Africa. This church is the spiritual home of Armenians in Egypt.

Continuing down Ramses Street and then moving much further east one enters Heliopolis, an area originally designed as an upper class suburb for Cairo which attracted many of Cairo’s cosmopolitan elite away from the hustle of downtown and has become the home of most Armenians in Cairo. A walk around Heliopolis will take one past many of the still operating Armenian clubs in the area where there are regular events, basketball matches and cultural activities. The Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) Egypt office can also be founded here. The organisation was founded in Cairo in 1906 by Boghos Nubar (Nubar Pasha’s son) to support the socio-economic and educational improvement of Armenians which they continue to do to this day in addition to many other programmes. Their office here also includes the organisation's archive which this project has researched to shine a light on the earliest period of the Sudanese-Armenian community.

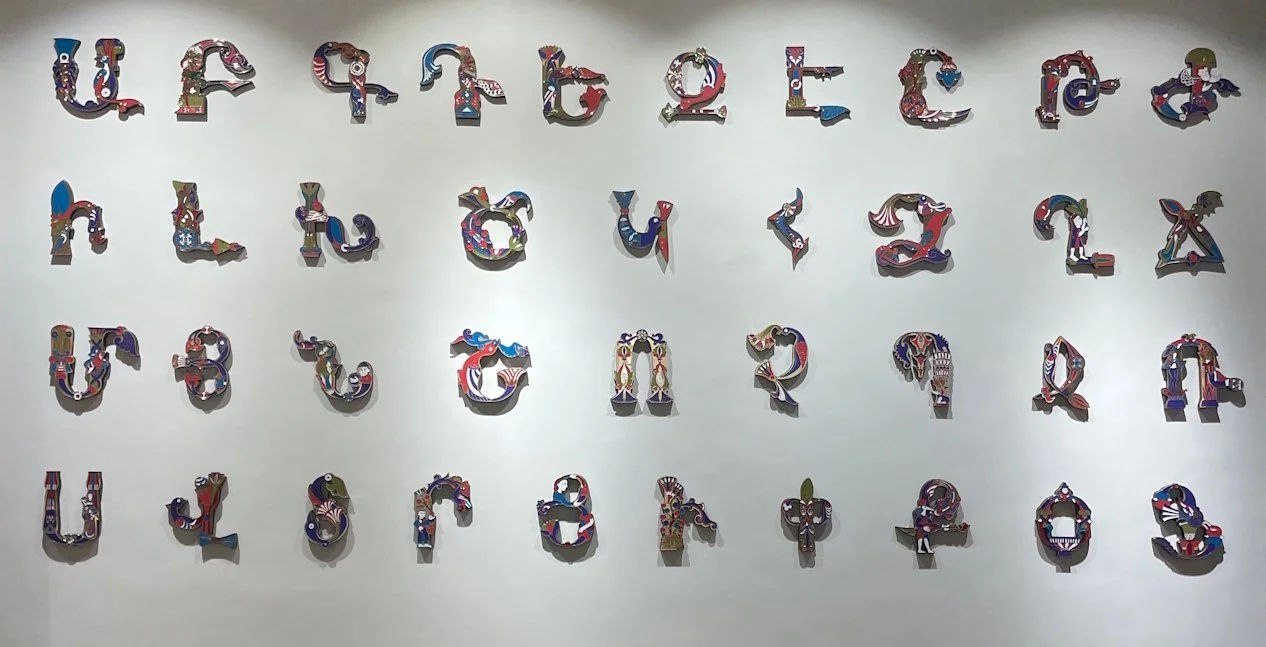

Though the Armenian community of Egypt’s numbers have reduced from its peak to approximately 5000, the community remains active and secures itself a future via the Kalousdian-Nubarian School in Heliopolis which merged the Kalousdian and Nubarian schools in 2012. The final stop on the journey through Armenian Cairo is also an unlikely one, Basturma Mano. Basturma Mano doesn’t represent a history or grandeur linked to a previous era. It is an Armenian restaurant chain famous in Beirut, and now present in Cairo as well. Staff from the Beirut branch work here in Heliopolis to ensure the quality that the brand is known for is maintained. It is a place where one can order sujukh or basturma sandwiches with a tan (yoghurt drink) in Armenian. Basturma Mano is a reminder that from food, to art, to architecture to business, the Armenians have a reputation for quality work in Egypt which continues to this day.

From Cairo to Khartoum

A few thousand words will never be anywhere near enough to cover this community and its rich legacy. Each business, building or name mentioned here has enough of a story to warrant a history of its own. And for each of those mentioned here, there are another five or ten that haven’t been mentioned. For those interested there are many documentaries, books and articles in the notes section to learn more about this community and its impact on Egyptian society. To know this impact, one only has to mention they are Armenian on the streets of Cairo, while in some countries the common reply might be to ask what is Armenia, or to say they have been Albania on holiday, in Egypt you will likely receive a reply that tells a tale of how respected Armenians are or an unsolicited lecture on the street about the history of Armenians in Egypt or about a respectable Armenian they once knew.

In the context of understanding the Sudanese-Armenian community, the Armenian community of Sudan was linked to Egypt via an imperialist structure in the period up until Sudanese independence in 1956. Many young Sudanese-Armenians studied in Egypt, many Sudanese-Armenian businesses were branches of those that existed in Egypt or vice versa, and many Armenians came and went between Egypt and Sudan facilitating cultural exchanges.

That said, the geographical barrier between Cairo and Khartoum limited interactions, much more so than other Middle Eastern communities that weren't as isolated. For example a drive between the Armenian cultural centres of Beirut and Damascus takes approximately two hours compared to the multiple day journey from Cairo to Khartoum. Nonetheless Egypt’s Armenian community was the largest influence on the Armenian community of Sudan. These familial, commercial and institutional links between the two communities were naturally stronger until Sudanese independence after which Sudan was not formally linked to Egypt. The communities share similarities in terms of their commercial success, that being rooted in being a foreign community that profited due to their ability to speak local and European languages, conduct business with Europeans, and apply their craft knowledge and skills during the ‘modernisation’ and economic growth of both countries. This wealth in turn was invested into community via schools, clubs and churches.

This article has aimed to provide a concise overview of the Egyptian-Armenian community’s history, offering a broad sense of its development and role within Egypt’s wider historical context. Given the richness and depth of existing literature, it is a challenge to approach the topic without delving further into its many layers. Rather than presenting an academically rigorous study, this article takes the form of a narrative journey through time and space. The following notes highlight some of the key sources that informed this piece and may serve as starting points for those interested in exploring the subject further.

Notes:

Many thanks to Salma Mohammed for helping with translating, guiding and navigating Cairo for this article. Credit to Jamal Mutassim for the artwork.

For early Armenian history in Egypt, including Badr al-Jamali, see Seta Dadoyan’s The Fatimid Armenians: Cultural and Political Interactions of the Near East. HyeTert has an article on Armenian Mamluks, and Walle and Hedrk have written a paper on Badr al-Jamali’s role in restoring the Fatimid state. For descriptions of Armenian churches in medieval Egypt, see Abu Salih al-Armani’s The Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and Some Neighbouring Countries.

For Armenians in 19th-century Egypt, including Nubar Pasha, see Mudhakkarāt Nūbār Bāshā (Memoirs: Nubar Pasha). For a modern biography, see Victoria Arsharoni’s Nūbār Bāshā: Khādim Miṣr al-Kabīr (Nubar Pasha: Great Servant of Egypt), translated into Arabic by Garo Tabakian. Rouben Adalian’s article leverages many sources to study the Armenians in Egypt during the reign of Muhammad Ali. Bedros Torosian’s In Search of Haven and Seeking Fortune offer overviews of Armenian life in Egypt during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sona Zeitelian’s Armenians in Egypt provides a comprehensive historical account, and Armin Kredian has written on the community during World War I.

For a detailed study of Armenian publishing and the press in Egypt, see the research and work of Souren Bairamian.

You can read more about the Papazian shop at the Facebook post here.

There is a documentary on the Kalousdian School from 1987 that can be watched here.

For Arabic-language sources on the Egyptian-Armenian community, including archival research, see the works of Muhammad Refaat al-Imam. For a Arabic language study of Armenian sports in Egypt a book was recently published in 2025 by Gamal Abd Al-Hamid.

For official information, see the Armenian Embassy’s website summary on the history of Armenians in Egypt. For journalistic perspectives, see articles by AGBU, Catherine Yesayan’s travel reflections in Asbarez, and Egyptian Streets’ feature with interviews from Egyptian-Armenians.

AGBU has a list of Egyptian-Armenian artists here.

For a wide-ranging collection of academic work, see the two-volume publication Armenians of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, edited by Antranik Dakessian and published by Haigazian University, featuring articles in Armenian, English, and Arabic.

For visual sources, see documentaries produced in Armenia about Armenian communities in Cairo and Alexandria. The short documentary Armanli is also available online. The 2016 documentary We Are Egyptian Armenian remains the most comprehensive film on the community’s history in addition to the ‘الأرمن في مصر’ documentary from 2025.

There are many more sources on the Egyptian-Armenian community in Armenian, English and Arabic. If you would like to find out more reach out via email at vahe@sudanahye.com.

Stay updated:

Stay updated on our latest releases - give our social media pages a follow.

We would love to hear from you, whether it be a reflection on this post, a correction or a suggestion, send us an email at vahe@sudanahye.com.