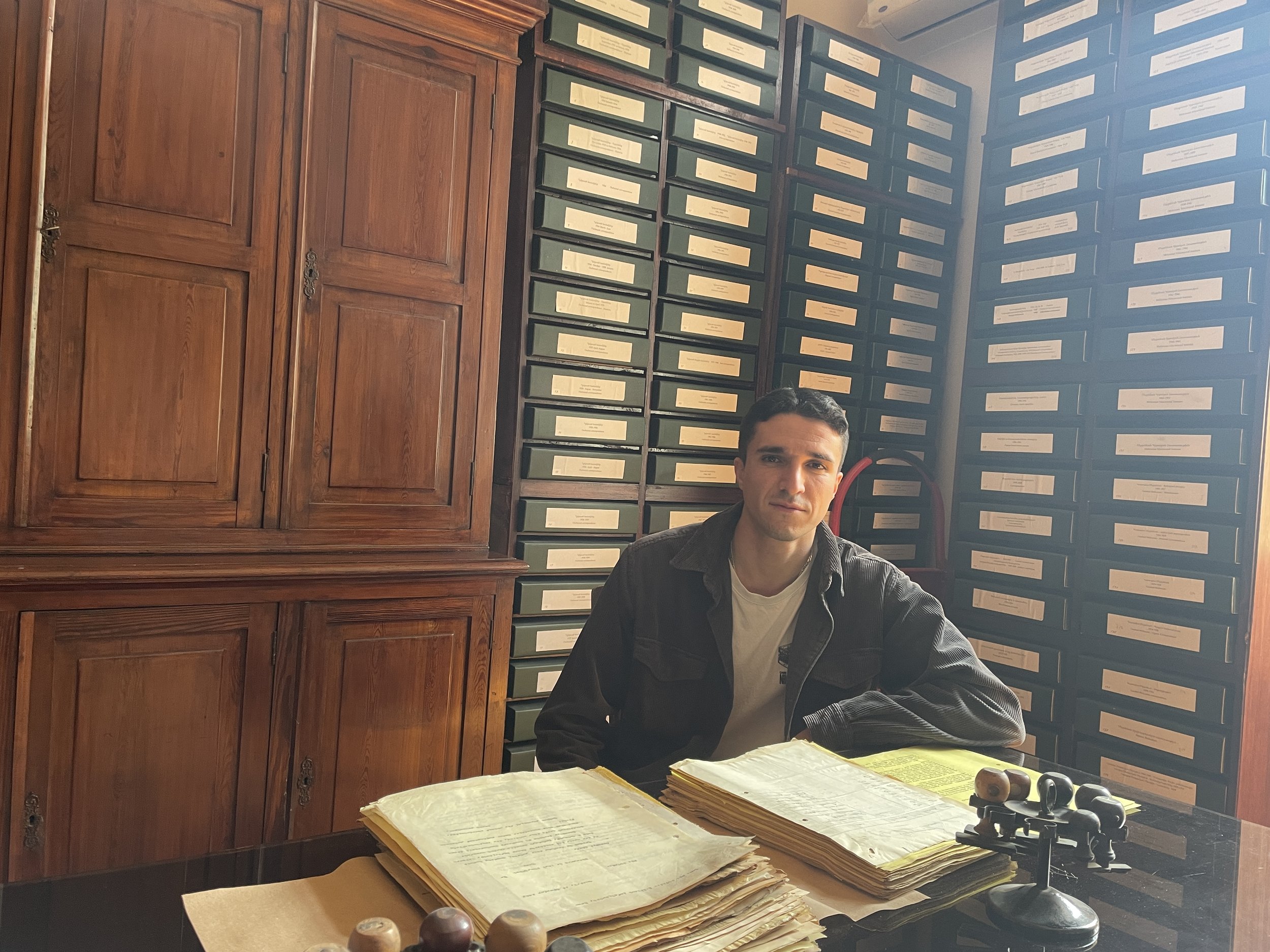

Yacoub Artin Chrakian: The Pasha in the archives

Having explored Yacoub Artin Pasha’s journey to Sudan and touching upon the context of other Armenian bureaucrats in Egypt, we will complete our series on Yacoub Artin Pasha with this article where we will explore him in the archives of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) in Cairo.

Discovering AGBU Sudan in the archives

AGBU is an organisation founded in Cairo in 1906 to work for the socio-economic and educational development of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. The organisation still exists today with a modified and expanded scope for the 21st century. The AGBU Archives in Cairo contains documents and letters from a number of countries that had AGBU branches since its inception. Due to the efforts of their archivist Maroush Yeramian, the Sudan branch’s archive has 735 documents. Many of these have been damaged or had ink run over the years but it still provides us an unparalleled resource to study the early Armenian community. Consequently this archive is an essential source which we will leverage heavily in researching Armenians in Sudan.

In the previous article, we learnt via Yacoub Artin Pasha’s travel to Sudan in 1908 about the early Armenians of Sudan. Most were traders and many were geographically isolated across Sudan’s vast geographies. Through the efforts of Dr Kevork Djerjian, AGBU Sudan was founded in 1909 to organise these Armenians, giving them a community institution and a means with which to support their suffering compatriots. Their initial activities were limited to fundraising from members and it took four years for them to hold their first event. As the communities numbers swelled following the Genocide, other community organisations were established which catered more to the needs of the Armenians in Sudan such as providing a community space, a school or a church rather than fundraising for relief of Armenian refugees which was the AGBU’s primary focus. Over the next five decades, AGBU Sudan primarily focused on fundraising and went in and out of periods of activity, generally dependent on the efforts of a few individuals such as Dr Kevork Djerjian.

The Lemonjian Affair

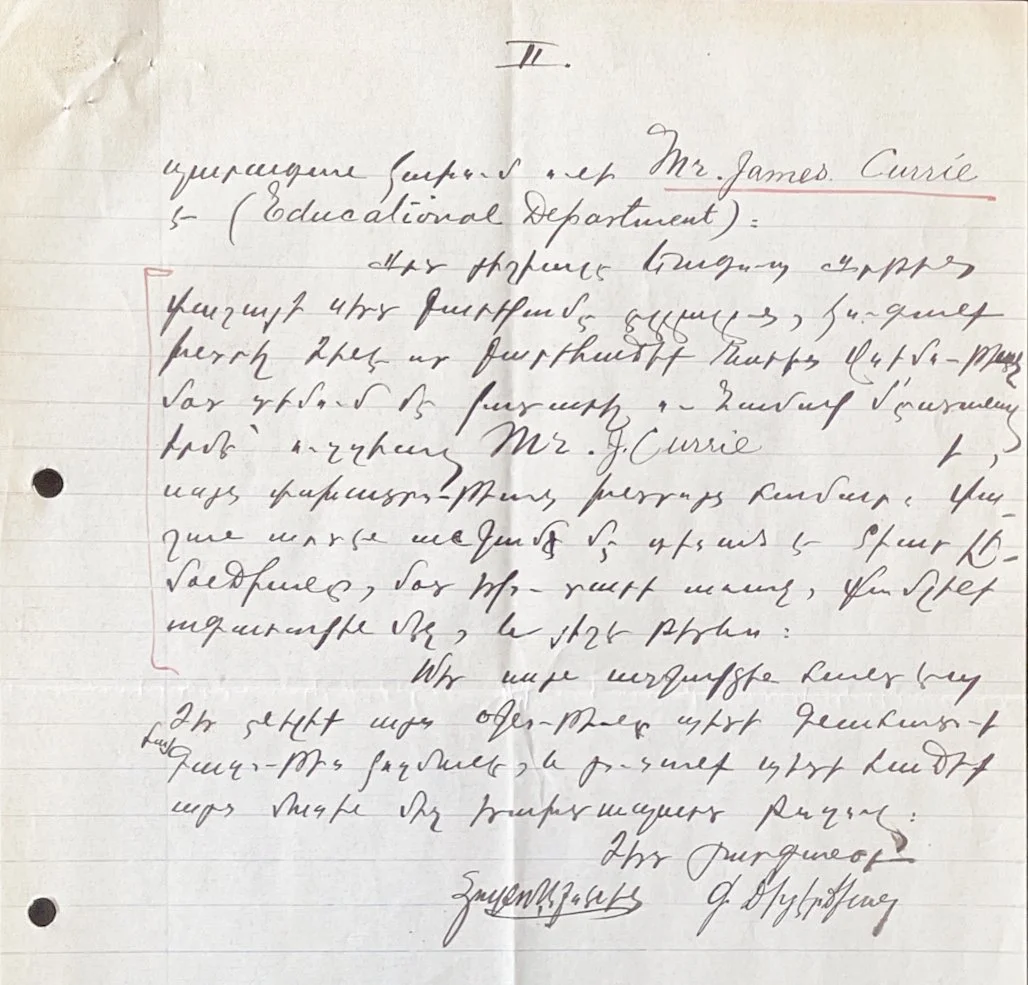

Description: The second page of Dr Kevork Djerdjian’s letter to AGBU Cairo asking for assistance with the Lemondjian affair

Location: Cairo, Egypt

Source: AGBU Archive

There is a letter in the AGBU archive from 15 April 1912 to a Mr Malezian in Cairo from Dr Kevork Djerdjian. The letter discusses Mr Lemonjian, a mechanic in a government farm in Kamlin alongside Mr Bozadjian. Having closed the government farm, Bozadjian and Lemonjian were sent to different locations with Lemonjian relocating with his family to Tayiba. The letter continues explaining that life was unbearable in Tayiba especially in light of Lemonjian having his wife and children with him. Lemonjian wanted to have his location moved to join Mr Bozadjian, however this was something that would require the approval of James Currie, the education minister in Colonial Sudan. The letter requests that AGBU in Cairo asks Yacoub Artin Pasha, then the Vice-President of AGBU, to speak to James Currie, a friend of his, to have Lemondjian moved to where Bozadjian is.

The letter states that Yacoub Artin Pasha is already acquainted with Lemonjian from his travels to Sudan a few years previous (you can read about this encounter in our article about his travels). The letter explicitly states that if Yacoub Artin Pasha can have this arranged, it will help AGBU in Sudan be viewed positively by the community.

The reply comes in a letter from 8 June 1912 from Cairo to Dr Kevork Djerdjian stating that Yacoub Artin Pasha sent a letter to James Currie on Lemonjian. AGBU Cairo say that they hope this resolves the matter and that Lemonjian will become a member of AGBU as a result of this intervention by AGBU. The archive also contains member lists of AGBU Sudan. These are an excellent source of information telling us the locations of Armenians in Sudan and how much money they were donating. The source is limited to the members who were AGBU but the member lists still provides us a proxy for a census of the community in this era. Via the member lists we have it appears Lemonjian did not join AGBU in 1912 or the subsequent years.

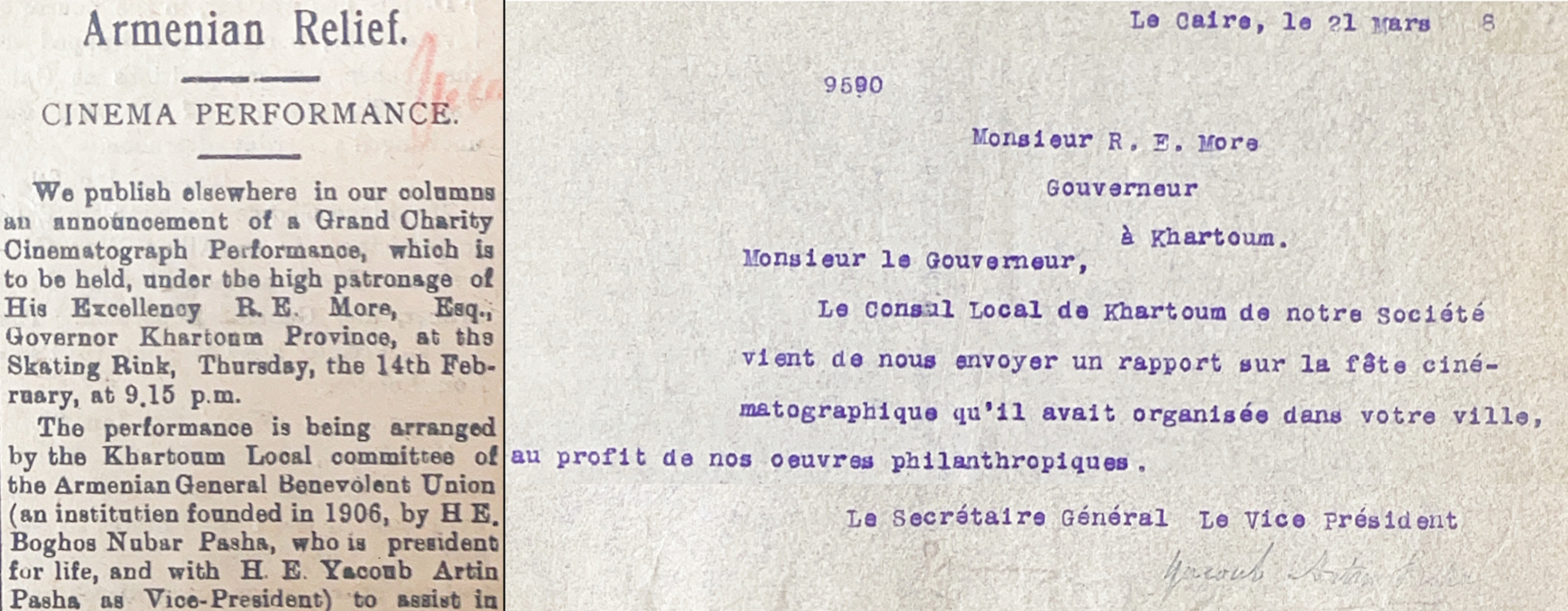

A cinematic thanks

On 14th February 1918 a ‘Grand Charity Cinematograph Performance’ was held at the Khartoum Skating Rink. The archive contains an advert from a British newspaper from Sudan in advance of the event stating that it was organised by AGBU under the ‘high patronage of His Excellency R.E More, Esq., Governor Khartoum Province’. It states that the ‘greatness of the cause for which this Cinema performance is being given, will be immediately apparent to our readers’ implying that the ‘sufferings of the Armenian Nation’ were known by the British in Sudan.

Following the event a grateful letter in French was sent:

“We were pleased to note that this event was crowned with great success, thanks to the patronage you were kind enough to grant it, and we feel it our duty to present to you, on behalf of our unfortunate compatriots whom the Union assists in their distress, our deepest thanks.

We like to believe that you will be willing to honor the members of our Union in Sudan with your sympathy in the fulfillment of their patriotic mission, and we beg you, Mr. Governor, to accept the assurance of our distinguished consideration.”

A cinema event in 1918 was likely an unprecedented affair for Khartoum. At this point there was not a purpose built cinema building as it was a relatively new technology with silent films in the skating ring being attended mostly by British and other foreigners. The Armenians being able to hold this event confirms what we know about the financial prominence and cosmopolitanism of the Armenians in Sudan even in this period when the community was still young.

Description: A shortened version of the letter from Yacoub Artin Pasha to Governor General More and the article in the British newspaper from Sudan advertising AGBU’s Cinema event

Location: Cairo, Egypt

Source: AGBU Archive

Abcarios or Abkarian?

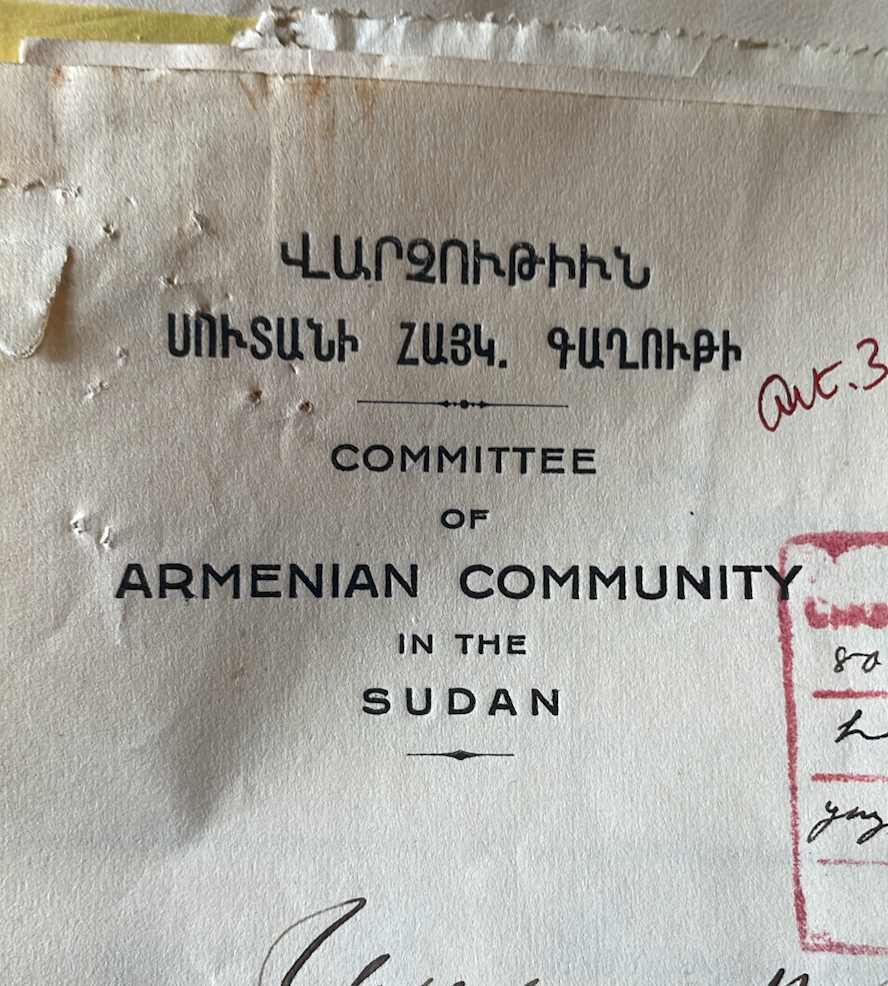

Description: A letterhead from the ‘Committee of Armenian Community in the Sudan’

Location: Cairo, Egypt

Source: AGBU Archive

Abcarios was mentioned as a judge in the Pasha’s travel to Sudan. He is not noted as Armenian in the book, despite Abcarios being an Anglicised version of the Armenian name Abkar or surname Abkarian. Away from the archives, Abcarios is mentioned in the book by A.Abrahamyan: ‘Համառոտ Ուրվագիծ Հայ Գաղթավայրերի Պատմության’ (A Concise Outline of the History of Armenian Diaspora Communities). The source states that with the increase in the number of Armenians in the 1910s they required an organisation with which to represent themselves to the British colonial authorities, who believed an Armenian representation wasn’t necessary. In 1912 on a visit to Sudan by Yacoub Artin Pasha discovered this situation through conversation with the Governor Wingate. Wingate suggested Yacoub Artin Pasha advise the ‘prominent lawyer’ Abkarios, to assist the Armenians. These efforts were only fruitful in 1917-1918 when an organisation was established, ‘The Committee of Armenian Community in Sudan’ and their constitution was presented to the British as the representative of Armenians in Sudan.

A Pasha in the archives

We know that Yacoub Artin had language skills, that he was respected by Egyptians, Europeans and Armenians alike and that in this period he was the vice-president of AGBU. But what we did not know was that he was a means for the Armenians in Sudan to gain favour with the British authorities. As discussed in the other articles in this series, Armenians operated in a gap created by the British, primarily a commercial one which placed Armenians as cross-cultural intermediaries, able and willing to interact with both British and Sudanese. But the Pasha’s involvement in affairs shows us how far the limitation of this de facto privileged position the Armenians had.

In the first case, in the Lemondjian affair, the Armenians call upon the Pasha to leverage his reputation with James Currie for the benefit of an Armenian in Sudan. This implies that the Armenian leaders in Sudan such as Dr Kevork Djerdjian did not have the connections or a suitable reputation with the authorities to attain favourable circumstances. In the second case, AGBU hosted a cinema event with the blessing of the British. The event is advertised for Khartoum’s cosmopolitan upper classes of British colonials and wealthy foreign communities giving us a sense of the Armenian socio-economic position. However, the letter from Yacoub Artin Pasha and its tone again suggests a limit to this because they required the weight of the Pasha’s reputation to appropriately show their gratitude to the British and their hope for continued patronisation going forward. The Abcarios story again demonstrates how Yacoub Artin Pasha used his connections with the British to push matters forward for the Armenian community. In this sense perhaps its best we view him as a senior advisor or ‘honorary president’ assisting and advising the Armenians on high level matters by being able to surpass the disorganisation and dynamics of the community.

Yacoub Artin Pasha’s life ended in Egypt on January 21 1919 at 77 years old. Despite the prominent role he had in Egyptian education reforms, and his scholarly works, he is not a famous figure in Armenian or Egyptian history. In contrast, Nubar Pasha, the Armenian Prime Minister of Egypt, is remembered in Egypt to this date as a figure who made significant contributions to Egypt and whose statue stands outside the Alexandria Opera House to this day. Nubar Street in Cairo matches his legacy, and is an important road in the downtown area. There is a road in the quieter areas of the Heliopolis area of Cairo called Yacoub Artin Pasha Street.

His final resting place is in the crypt in the Armenian Catholic Cemetery in the Fustat area of Cairo, a cemetery whose graves speaks to the achievements, opulence and wealth of the Armenians of Egypt in this period. Beyond being vice-president of AGBU, he was a strong supporter of the Armenian Catholic community of Egypt and his privileged resting place in the crypt in the centre of the cemetery is a symbol of his commitment to his Armenian identity.

Notes:

You can read more about AGBU’s history at their website here and their current activities at the here

Antranik Dakessian of Haigazian University wrote a chapter titled ‘Փոքրապատում Սուտանի Հայօճախի ՀԲԸՄ Մասնաճիւղի (1909-1945, 1957)’ or ‘A small story of AGBU Sudan Branch (1909-1945, 1957)’ in the 2nd volume of A.Dakessian, Armenians of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia Proceedings of the Conference (12-13 April and 29-30 May 2018) (Haigazian: Beirut, 2022). The book has four papers on the Sudanese-Armenian community. A.Dakessian’s paper aims to ‘reconstruct the micro-history of the AGBU Sudan chapter’ based on the archive in Cairo and is an excellent introduction for this projects more thorough analysis and research of the documents in the archive. The paper focuses on the tensions between AGBU’s fundraising efforts and the directing of resources for the domestic needs of the community.

For more on Dr Kevork Djerdjian, one of the community pioneers, including his journey to Sudan and his photo collection from his life in Ottoman Armenia see our article about Arabkir’s Armenians in Sudan here.

The Sudan branch’s member lists from the AGBU Archive are an excellent resource telling us the locations of Armenians in Sudan and how much money they were donating. The source is limited to the members who were AGBU, there are some years missing and the format is not consistent, however they still provide a proxy for a census of the community in this era. In 1914 and 1915 in Gedaref there is a ‘Yousef Artin’ listed as a merchant in these member lists. Yacoub Artin Pasha’s brother was called Yousef Artin, and in Yacoub Artin Pasha’s text about his Father which we translated here, he states that his younger brother: ‘Yusuf Artin Bey, born in Alexandria in 1844, who from 1876 onward was established in India.’ Could this be the same Yusuf Artin at age 70 operating as a merchant in Sudan? It is impossible to tell based on the information we have.

For more on the history of Sudanese cinema see Elmustafa Elsheikh Hayaty, A. , Yin, C. , Ullah, Z. , Ahmed, S. and He, T. (2021) Sudanese Cinema: Past, Present and Future. Art and Design Review, 9, 268-283. To see pictures of the history of Sudanese cinema see this link from Sudan Memory. In 2025 Modern Sudan Collective hosted a conference ‘Conversations Modern Cinema’ which included talks on the history of Sudanese cinema, you can see the schedule and talks from this event here.

A. G. Abrahamyan, Համառոտ ուրվագիծ հայ գաղթավայրերի պատմության (Yerevan, 1964) can be accessed here.

For more details on Abcarios see A. Bakchinyan, Հայերն Աֆրիկայում (Yerevan, 2024).

There are also more direct letters from Yacoub Artin Pasha to AGBU Sudan in French in the archive - these are generally acknowledgements and formal replies that do not add to our understanding of the history.

Nubar Pasha’s statue was missing for decades following Nasser’s revolution before being reinstated outside the Alexandria opera house. You can find out more about this via our reel here.

Stay updated:

Stay updated on our latest releases - give our social media pages a follow.

We would love to hear from you, whether it be a reflection on this post, a correction or a suggestion, send us an email at info@sudanahye.com.